Aromatic Metamorphosis: Queer Men, Masculinity & Botanicals in Ancient Greece

- Nuri@Atropos

- Dec 3, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 5

Ancient Greek religion was deeply eco-centric. The environment was considered sacred and therefore worthy of mythologisation. In this worldview, plants contained both pneuma (life spirit, soul) and archē (the life-giving force that distinguishes plants from inanimate objects). Aromatic plants were believed to contain greater concentrations of pneuma and archē, which were the sources of their scent. From this perspective, odour was not simply a part of the plant's aesthetic quality but evidence of its spiritual potency.

These botanical odours served as proof of the porous boundaries between humans, gods, and the natural world. This is why aromatic plants were so frequently used in ritual. They could both ground the experience in the ecology of Greece while transcending into the ethereal. Every culturally significant aromatic plant in ancient Greece had a mythic origin story, and all of them involved transmogrification and tragedy, but why? Well, metamorphosis imbued the plant's pneuma with human character, anchoring it in deep emotions, often romantic or erotic. Likewise, tragedy served as the emotional and spiritual fuel behind the story's drama.

Thus, the human experience became embodied in the sacred landscape, and those aromatic botanicals could connect people to concepts embedded in their narratives. We see a unique facet of this emeshment reflected in the queer-focused myths of Ampelos (grape vines), Hyacinthus (hyacinth), Narcissus (narcissus), and Cyparissus (cypress).

Queer Love & Myth in Ancient Greece

Love, death, and mercurial deities are central to these botanical metamorphosis stories. While many revolve around heterosexual love, several centre on male homosexual relationships. Within these tales, we see the characters play the well-known romantic roles of the erastēs (lit. lover, the active/penetrating partner) and erōmenos (lit. beloved, the passive/penetrated partner). Erastēs/erōmenos relationships were common in ancient Greece and involved an imbalance of power. Erastai were often older, wealthier, and more experienced than their beloveds, and the relationship involved both romance and mentorship.

While often framed as pedophilic in modern popular media, erastēs/erōmenos relationships were consensual and between individuals of sexual maturity in their societies. In Athens, it was common to become an erōmenos after military training at the age of nineteen or twenty. The erastēs might only be in his early to mid twenties, and thus the age difference between the two lovers was often negligible. These relationships would traditionally last for several years as the erōmenos established himself in his trade and usually ended when he married. In ancient Greece, desire for homosexual love and sex did not negate one's familial responsibilities to have children.

While mentorship and initiation into adulthood were part of these relationships, they were not strictly transactional. The Sacred Band of Thebes was an elite infantry unit composed of 150 pairs of erastēs/erōmenos couples who served together well into their thirties. Should one member of the pair fall in battle, it was reported that his lover would fight with a suicidal frenzy to avenge him and join him in the afterlife. We also know of many historical couples who maintained relationships for their whole lives. Like any cultural institution for romance, individual experiences varied widely.

Within these aromatic myths, the god is most often the erastēs and the ill-fated mortal the erōmenos. As the erastēs, the god is the lover and mentor to the beloved, but also his deity. Rarely do they do all three roles well. As the erōmenos, the mortal lover is the stand-in for humanity, and thus serves as a parable to teach proper and improper behaviour. Ultimately, the tragedy in all of these myths comes from the erōmenos' failure to behave like a proper Hellenistic man.

Framing intercourse with the divine as a romantic relationship is not unique to Greece; we see this, for instance, in the Song of Songs. However, the Greek deities (male deities in particular) are unique in their casual bisexuality. Yet, ancient Greece was not a Shangri-La of sexual expression. Even as these myths use erastēs/erōmenos relationships to immortalise homosexual love, they also rely on homophobia born from a vicious loathing of the feminine to fuel the tragedy. This reflected real social hypocrisies people had to navigate. The status of the erōmenos could be extremely precarious, and the myths focus on that tension.

Do Not Move With Shame

The ideal erōmenos was beautiful, breadless, and sensitive. His desirability, however, could elevate him or invite divine jealousy, mortal rivalry, and metaphysical danger. This danger arose from the erōmenos' role as the passive partner. To be penetrated was to align one's self with femininity. In a society that saw masculinity as the pinnacle of existence, the erōmenos was both desired and treated with suspicion, as if a traitor to men. Therefore, the tragedy of these aromatic tales befalls the erōmenos due to, as the Greeks saw it, the fatal character flaw of effeminacy.

The word for effeminate in Koine Greek is kinaidos, a compound word deriving from kineō (move) and aidos (shame). To be kinaidos is to be one who moves through the world shamefully, and it was exclusively used as a derogatory term for effeminate erōmenos. Kinaidos denotes a man emulating the body posture of a promiscuous woman. Someone with a mincing gate, wiggling bottom, swinging hips, and a careless and chatty disposition. So the erōmenos by his very nature must be erotically desirable to his active partner, but still must maintain the strict bounds of masculine gender expression. In Grindr parlance, ancient Greece was strictly Masc4Masc. Yet, aesthetics and posture were not enough; one must think, emote, and moralise like a man.

The tension in ancient Greek society between desire for the erōmenos and disgust for the kinaidos is essential for understanding these queer aromatic origin myths. Yes, they are love stories grappling with loss, but they are laced with warning. The erōmenoi of these myths each possess a feminine flaw that triggers the tragedy, such as vanity, pride, promiscuity, or emotional volatility. These kinaidos traits reveal how deeply misogyny shaped Greek perceptions of queerness. The myths below used nature to memorialise queer longing while simultaneously disciplining it, reminding men of acceptable and unacceptable forms of homosexual desire.

Dionysus & Ampelos

The Tragic Flaw of Being A Brat With Catty Friends

Many are unaware that Dionysus's devotion to wine originates in his eternal mourning for his lover, Ampelos (lit. vine). Ampelos was a young and beautiful satyr with whom Dionysus fell deeply and possessively in love. The texts repeatedly emphasise Ampelos' physical beauty and his odmê d'imeroessa (scent of desire). His fragrance becomes an index of queer longing: Dionysus's longing for him, and the plant's future potential to evoke longing in others.

Dionysus becomes preoccupied with keeping Ampelos safe, fearing he might suffer the same fate as Zeus' beloved Ganymede. Hera, still harbouring resentment toward Dionysus, sends Ate, the spirit of Delusion, to corrupt Ampelos. Ate is the prototypical toxic friend, amplifying his worst traits. She encouraged Ampelos to feel invincible and entitled. This culminates in him insulting Selene and attempting to ride her sacred bull, which ends with him being gored to death.

Despondent, Dionysus fills Ampelos' wounds with ambrosia to preserve his beauty and fragrance. From the ambrosial wounds grapes formed; his body became the stalk, and his limbs the vines of the grape. In Dionysian rites, worshippers were instructed to smell the wine as a way of encountering Ampelos' lingering odmê d'imeroessa, a ritualised inhalation of queer desire, grief, and devotion.

While a tragic love story, the myth also warns queer men against the traits associated with the feminised, undisciplined erōmenos: hubris, entitlement, and reckless speech. These were considered destabilising to masculinity and society.

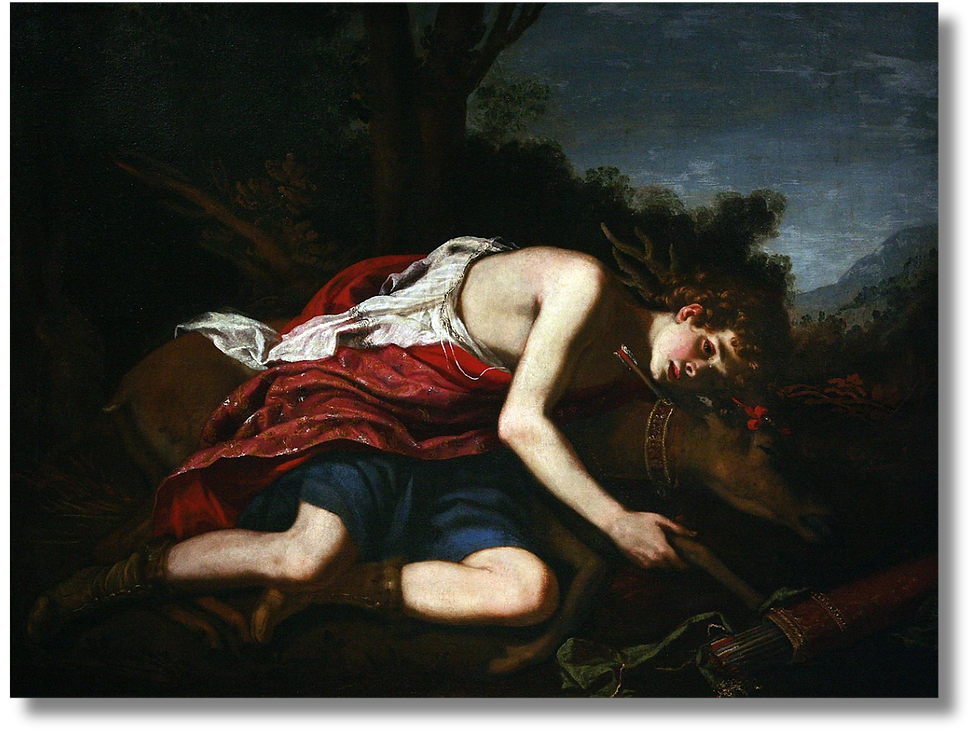

Apollo & Hyacinthus

The Tragic Flaw of Being Hot & Having an Ex

Hyacinthus, a Spartan prince renowned for his extraordinary beauty and distinctive scent, became the beloved of Apollo. His flaw was simply that he was too desirable. His beauty captivated too many: Zephyrus, Boreas, and even the mortal singer Thamyris. In some versions of the story, Hyacinthus is already Zephyrus' lover before meeting Apollo and leaves the west wind for him. Like Dionysus with Ampelos, Apollo becomes so enamoured that he abandons his prophetic duties at Delphi to spend idyllic days with Hyacinthus by the river Eurotas.

As Apollo and Hyacinthus engaged in a friendly game of discus, Zephyrus, wracked with jealousy and desire, blows Apollo's discus off course, killing Hyacinthus. Ancient commentators imply that the cause of the tragedy is a combination of Apollo's negligent obsession, Zephyrus' jealousy, and the malevolent evil eye cast by multiple spurned lovers. All of which ultimately derives from Hyacinthus being too attractive and too immodestly visible to others. The ancient equivalent of, "but what was he wearing?"

Apollo desperately tries to save him with medicine and ambrosia, but Hyacinthus' fate is sealed. From his blood, Apollo creates the hyacinth flower and inscribes on its petals the lamentation AI AI (lit. alas).

Hyacinthus' crime was simply the peril of queer desirability: to be beautiful enough to attract a god is also to be beautiful enough to incite violent longing in others. The myth implicitly warns queer men not to be too desirable, lest beauty provoke dangerous competition or divine jealousy. A queer man's allure was to be moderated, enough to charm, but not enough to threaten.

Narcissus & Ameinias

The Tragic Flaw of Being Stuck Up & Bitchy

In a rare story involving two mortals, Narcissus, famed as the most beautiful youth in Thespiae, is often read through a modern asexual lens. However, ancient sources depict him as a messy bisexual with no shortage of sexual interests. He simply believed no one was good enough for him. He also has a cruel streak.

When Ameinias approached him seeking to become his lover, Narcissus not only rejected him but mockingly gave him a sword. Ameinias used it to kill himself on Narcissus' doorstep, praying to Nemesis for justice, "May Narcissus experience the pain of longing and rejection he inflicted on others." Nemesis, rarely invoked but always creative in her punishments, answers this prayer. She drives Narcissus to fall in love with his own reflection. In early variants, he realises his beloved reflection is unreachable and dies by suicide, and from his remains, his namesake flowers grow. In later tales, nymphs transform him into the flower, softening the tragedy. Roman retellings frame his suicide as remorseful, suggesting the flower springs from the pnuema of his repentant blood. The heady odour of the flower becomes a symbol for both beauty and dangerous self-obsession.

The moral: the erōmenos must not be conceited. An erastēs' desire required grace in rejection, and an erōmenos must have humility in the face of longing. To mock or scorn another man's desire for you was to invite cosmic retribution.

Apollo & Cyparissus

The Tragic Flaw of Being Sympathetic & Sensitive

The story of Cyparissus, another beautiful youth loved by Apollo, deepens the pattern of queer longing and tragic metamorphosis. Cyparissus is consistently described as gentle, strikingly handsome, and emotionally sensitive, traits that marked him as an ideal erōmenos but also rendered him vulnerable to the moralising narrative that governs these myths.

Apollo gifts Cyparissus a magnificent sacred stag, a companion that becomes the centre of his world. The intimacy between Cyparissus and his pet is depicted with the same tenderness reserved for lovers. The stories emphasise Cyparissus’ emotional openness and capacity for deep attachment, and it is this intensity of emotion that becomes his downfall.

While hunting, he accidentally kills the stag with a misthrown spear. Overwhelmed by guilt, he collapses into inconsolable grief. Apollo attempts to comfort him and offers him divine forgiveness, but Cyparissus refuses and begs his lover to place him in a permanent state of mourning. Apollo reluctantly grants his wish to weep forever, turning him into a cypress tree. The trees' drooping leaves symbolise his downturned body, and the heady aroma of the bark becomes the miasma of his endless sorrow.

Not only does Cyparissus transgress through feminine emotions, but through a child-like sentimentality and aversion to violence. Cyparissus isn't just behaving like a woman, but like a little girl. The myth of Cyparissus can be viewed as a coming-of-age metaphor in which Cyparissus failed to launch himself into manhood. A man hunts; he does not mourn the hunted.

Cyparissus’ tragic flaw is not vanity or arrogance but unregulated emotional excess. His inability to recover, to moderate his emotions, and resume his socially expected path into maturity becomes the catalyst for divine intervention. While Apollo’s love immortalises Cyparissus, the transformation also disciplines and chastises him. The myth encodes a warning to the listener that emotional abandon in the erōmenos invites metaphysical danger.

As the Story Goes

These myths reveal how queerness was simultaneously celebrated and constrained in ancient Greece. The erōmenos, whose desirability animated the story, was also doomed by his proximity to the feminine.

By transforming queer youths into aromatic botanicals, the Greeks memorialised same-sex love within the landscape while embedding cautionary lessons about masculinity, self-restraint, and the limits of acceptable behaviour. The fragrant plants born from these mythic deaths became sensorial reminders of the fragile position held by effeminate queer men in the ancient world. They were cherished enough to be immortalised, yet burdened with moralising narratives of excess and vanity.

These myths ultimately show how the natural world became a canvas onto which the Greeks projected their own unique sociocultural psychodrama. That drama held both their reverence for queer longing and their anxiety about its disruption of masculine gender norms. Aromatic metamorphosis thus occupies a paradoxical space, elevating queer desire into sacred memory while disciplining it through tragedy.

Upcoming Class

.png)

Comments