Gardens of Adonis: Women, Death, & the Senses

- Nuri@Atropos

- Sep 2, 2024

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 5

Every summer in ancient Athens, strange gardens emerged in courtyards and on rooftops. Seedlings were precariously sown into handfuls of soil within clusters of broken pottery. These impromptu micro gardens were lovingly tended for several weeks, yet they were created to be infertile and die. Long before they could bear fruit, the seedlings would wither under the intensity of the Hellenic sun or fail to take root in their shallow beds. The death of these eccentric gardens was the point, however. These were the Gardens of Adonis, and they provide us with a unique insight into the complex lives and experiences of ancient Athenian women.

The Adonia

Every year in July, the women of Athens gathered to celebrate the Adonia, a festival ritually mourning the death of Adonis. The Adonia was an unofficial festival celebrated in domestic spaces by women. The festival centred on themes of loss and hope, life and death, fertility, the fragility of life, and impermanence. It was a deeply social event focused on shared emotional catharsis for women. This was decidedly different from the traditional life cycle festivals that glorified women’s physical and emotional labour for, and duty to, others. The Adonia was a way for women to mourn elements of their personal lives and share in the catharsis of mourning as a group. Did you ever see Midsommar? Remember when all the girls were crying on the floor? Similar vibe.

The Adonis Gardens were planted several weeks before the Adonia, creating a miniaturised sacred space within the home. Fast-growing plants, symbolic of fertility, death, and the transience of life, were planted in these gardens. Lettuce, fennel, dill, cress, and onions were popular choices. Saffron and myrrh, aromata deeply tied to the myth of Adonis, would be sprinkled on these scenes, adding colour and scent. The Gardens of Adonis were tended by the household’s women, including servants and slaves. Adonis held a dual nature in the minds of the Greeks, representing both youthful beauty and impermanence. Unsurprisingly, the central activity at his festival was to nurture the garden while contemplating beauty and the inevitable decay of life. The wilting plants mirrored the tragic death of Adonis and the joy promised in his return.

On the Adonia, the women of the city would gather up their potshard gardens and carry them along with icons of Adonis in a ritual funeral. Some mourners wore black or saffron-dyed robes; others placed saffron powder in their hair. Myrrh was burned at the head of the procession. The pageant ended with a ritual burial at sea for the icons and shards. Then, female friends and extended relatives shared a meal at home.

These acts seem familiar to us today. Anyone who has seen an Orthodox saint’s feast or a funeral in the Eastern Mediterranean can see familiar elements at work. In the Greece of 400 BCE though, these were not common practices, and it is unclear if they evolved out of a unique Athenian experience or were imported from further East.

Regardless of their origins, in mourning Adonis, these women also mourned the losses in their own lives and the pain common to women at the time:

Children who did not survive

Relatives taken too soon

Loneliness

Young loves denied by their fathers

Cruel or indifferent husbands

The loss of beauty, youth, or health

The life decisions that society said they could not make for themselves

Adonis stood in for the kind lover they never had. He was their dreams left unfulfilled and their dashed hopes. In mourning him, they mourned for themselves.

The Sensuality of Mourning

Ancient Greek religious practices were deeply embodied. One should see, hear, smell, taste, feel, and envision the ritual at hand. To achieve this, formal religions in Greece used a host of theatrical techniques to heighten the experience. This included architecture, natural settings, art, statuary, puppetry, dress, masking, bathing, anointing, incense burning, sacrifice, dancing, song, chants, music, pain, pleasure, alcohol, drugs, and sex.

For instance, multiple cave temples around the Hellenic world were dedicated to Hades. The two best-known are the Charonion in Thymbria and the Plutonion in Hierapolis. These temples were gates to the underworld, whose natural and man-made architecture created a dramatic and dark chthonic world. One could enter and enact a passion play of descending to the underworld with the aid of a masked priest. This was done to commune with the god, gain wisdom, process grief, or ask to be released from life. Echoing chants, whispers, water, mysterious tableaux, and low lighting added to the experience. These caves also had CO2-leaking fissures. Exposure to natural gas would have altered the visitor’s cognition, making them more susceptible to suggestion and visions. This, of course, was precisely why these locations were chosen.

They made the mythical world real. The ritual was experiential. Indeed, travelling too deep into these cave systems was a sure way to meet Hades.

The Adonia was low-budget compared to the shenanigans at the Plutonion, but it still represented a deeply embodied practice. As Parker noted, the gardens themselves were experiential and served as a medium in which the women could physically interact with the concept of transience.

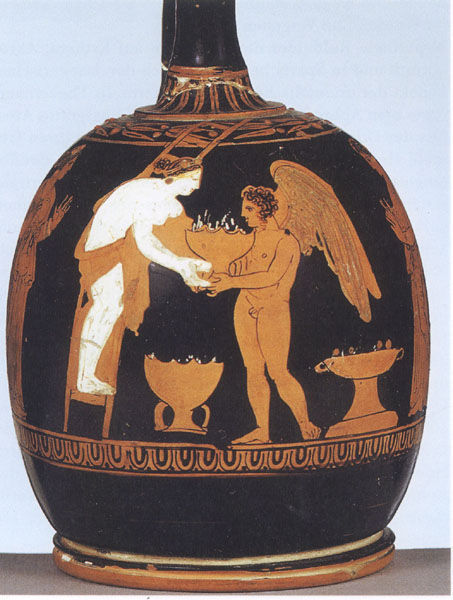

The women collectively created a visual scene that included bright spring greens, orange terracotta, black dirt, and yellow saffron powder. They had control over how they decorated the space. Perhaps there were icons of Adonis and Aphrodite or lamps in the evening for night-time contemplation. Because this wasn’t a formal altar with strict aesthetic rules, the gardens could be personalised.

Intermingling with the odour of saffron and myrrh was the scent of the decaying plants, which would have grown stronger as the Adonia approached. Olfactively witnessing this decay was part of the contemplation. The festival was a multi-sensory experience, with the scent of the decaying plants serving as a reminder of the transience of life. Scent was seen as an intermediary fluid between the mortal world and the divine in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean. Gods communicated to mortals through odours all the time. They ingested burnt offerings through divine olfaction. Scent was a completely legitimate way to access knowledge in the ancient Mediterranean. Sitting with the odours of the garden gave the women the potential to access both philosophical knowledge and divine revelation.

One could be immersed in Adonis’ presence by invoking his odour with saffron and myrrh. Aphrodite was strongly associated with frankincense and roses. Those odours may have been added to the gardens to create an olfactory tableau of the lovers. The growing stench of rot was Adonis’ mortality, wounding, and ultimate death. Anointing was likely part of these rituals. If icons were present, they most certainly would have been anointed, but the women may have also ritually fragranced themselves. Through the choice of fragrance, they could embody the role of one of the deities. Perhaps they were drawn to the tragic fate of Adonis, the deep sorrow of Aphrodite, the jealousy of Ares, the frustration of Hades, or the loneliness of Persephone. Symbolic odours and botanicals created an alignment between divine and human emotions.

Through this olfactive imagery, the participants could experience the beauty of youth, the moment when lovers meet, and the sorrow of their parting. Through this experiential retelling, they could also draw parallels to their own lives and find meaning and solace in the process. The embodiment of the procedure would have made these connections evocative and emotional.

Little is known about the communication between the participants, but all accounts of the Adonia in antiquity highlight the communal nature of the act. Women likely gathered around these gardens to share stories and comfort one another. Perhaps there were songs, prayers, or retellings of the myth. The gardens and the Adonia gave Athenian women a means to engage with their sorrows personally and collectively through ritual.

Why Adonis

At first blush, Adonis seems like a strange character for a religious Mary Sue. It is even odder because Adonis had no temples, formal cults, or priests in Greece. As far as we know, this was his only ritual. Why? Adonis was a late import to the Hellenic Mythos, and frankly, Persephone was already doing his job. Yet, because he was the new guy in town, there was more opportunity to reinterpret his myth to fulfil human needs that were not represented in the official rituals.

Aphrodite worship didn’t emerge in Cyprus until after the first Greek Dark Age, and Adonis worship followed. For perspective, Demeter had been worshipped in mainland Greece for at least 2,000 years by that point. Aphrodite was the synchronisation of a Cypriotic chthonic goddess with the Semitic Astarte. Astarte was herself a synchronisation of the Mesopotamian deity known as Ishtar or Inanna. Adonis bears his Semitic association in his very name; Adonis comes from the same root as the Phoenician Adon and Hebrew Adonai. All three words mean Lord.

Adonis was known as Adon in Phoenicia and Dumuzid (later, Tammuz) in Mesopotamia. Despite this heritage, the stories of Dumuzid and Adonis’ trips to the underworld are quite different and show significant disparities in how love, power, and gender were conceptualised in Hellenic and Mesopotamian societies.

In Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld, Inanna goes to the Land of the Dead on a mission to enrich her power, but gets tricked and killed. Her lover Dumuzid, does not properly mourn her by crying. To return to the living, Inanna must send an emissary to her sister’s court in her stead. When she finds out about Dumuzid’s faithlessness, she orders demons to drag him to hell. In The Return of Dumuzid, Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Dead, falls in love with Dumuzid while in the underworld. Yes, she had a husband and co-ruler, Nergal, but that didn’t matter. It is Ereshkigal calling the shots in the Land of the Dead. Eventually, Inanna’s rage subsided, and she became jealous of Ereshkigal’s affair with Dumuzid. So, the two sisters worked out a custody arrangement to share their lover. Dumuzid takes almost no action in the story—there are just two powerful goddesses who happen to be fighting over him. Inanna is not formally married to Dumuzid and has no children. Nergal isn’t a character in these myths; even their father, Enlil, cannot directly interfere with their fight.

In Adonis’s story, Ares’s sexual jealousy causes Adonis’s death. Aphrodite is despondent and travels to the underworld to plead with Hades. Hades is willing to break the rules and return Adonis, but only because Persephone had fallen in love with the mortal. However, Persephone defies her husband and refuses to surrender her lover. Eventually, Daddy Zeus needs to step in and work out a 50/50 split.

In a more disturbing version of the story, Aphrodite finds Adonis as a child and falls in love with him. She gives the baby to Persephone to raise until he is an adult, but Persephone also falls in love with the infant Adonis. When it was time for Aphrodite to retrieve her barely legal boyfriend, Persephone would not give him up, and again, Zeus worked out the situation.

In the Greek version, Ares, Hades, and Zeus are the players. Adonis is still passive, but so are the goddesses. Neither goddess controls their domains nor has complete control over their sexual lives. They both need male deities to intervene and adjudicate the situation. These divine women reflect the lives of mortal ones. Athenian women had little choice in their partners and almost no legal rights. Their identities were defined by the roles they played for others: mother, daughter, wife, servant, or slave. Women had limited ability to make changes in their own lives. They couldn’t officially buy anything more expensive than a loaf of bread. They had to work through the intermediaries of their fathers, brothers, husbands, uncles, and sons.

Minor children were the property and responsibility of their closest male relative. Girls were consulted, but ultimately did not decide who to marry. Athenian women typically married their first husband at 14. Their husbands were usually in their 30s. Girls were told to look to and obey their husbands like he was their new father. He was old enough to be their father, after all. The line between parent and spouse was uncomfortably blurred.

Women could initiate divorce and leave with their dowries, but they would have to return to their closest male relative’s care. They could not live independently nor have access to their children. So, women rarely left. Their fathers could also divorce them from their husbands against their will and give them to someone else, even if they had children and their husbands objected.

In mourning Adonis, Athenian women put themselves in the place of Aphrodite and Persephone, mourning their lost loves and their lack of autonomy. Neither Aphrodite nor Persephone chose their spouses and, by all accounts, would not have married Hephaestus or Hades if Zeus had not forced them. Even as married women, the goddesses are subject to their fathers’ rule, just as mortal women were.

The alternative telling of the myth strikes of emotional incest, with the goddesses trying to make the perfect companion and champion out of their foster son. Most Athenian women had more than one husband in their lives. However, should they become a widow and be unable to remarry, they would become wards to their adult sons. I don’t think it is hard to imagine women trying to build close relationships with their sons, not just for love but as a means of survival. Some surely burdened their sons to become the protectors and companions they needed their fathers and husbands to be. Again, the line between parent and spouse was uncomfortably blurred. The fight between Aphrodite and Persephone can be viewed as a battle between a new bride and her mother-in-law. Adonis is destined for Aphrodite, but Persephone’s incestuous love will not allow her foster son to leave her. Athenian women had reason to fear an incoming daughter-in-law as a real disruption to the little power they had. It must have been easy to see them as competition when both mother and wife needed the son to survive.

The stories of both Adonis and Persephone resonated so much with Athenian women because it was a mythic parallel to their own lives.

A Woman’s World: Between Persephone and Adonis

In many ways, Adonis and Persephone were mirrors of each other, and their festivals also served as counterbalanced lifecycle rituals for women. The Thesmophoria was the annual autumn festival dedicated to Demeter and Persephone. Like the Adonia, the Thesmophoria was celebrated only by women and centred on fertility and rebirth. Both festivals celebrated life and renewal with an acknowledgement of death and featured ritual elements of decay. For Persephone, that manifested as the rotting remains of sacrificial pigs spread over fields. For Adonis, it was the wilted death of his gardens, but the death and odour were spiritually significant to the rituals.

However, the Adonia differed from its sister festival in several ways. Firstly, Athens shut down for three days for the Thesmophoria; the state paid for processions and feasts. All of the temples and cults participated. Demeter was also much more selective, and ritual participation was limited to the wives of citizens. Enslaved women, foreigners, prostitutes, and maidens were forbidden from partaking in the Thesmophoria.

The Adonia, however, was for every woman regardless of status, and women of all walks of life participated. There were no public feasts. Instead, the Adonia happened at home, using kitchen scraps and potshards. The women of the Thesmophoria took a vow of secrecy never to share the details of the festival rites. The Adonia is also somewhat secretive, not because of vows, but because it was a festival that took place within the domestic sphere of women, which made it invisible to the eyes of official Athenian society, which was public, civic, and male-oriented.

The Thesmophoria and the Adonia reflected opposite experiences of womanhood, which nearly every woman in Athens would have related to. Demeter and Persephone represented the ideals of womanhood: perfect mother, perfect daughter, perfect wife. A woman’s existence is defined entirely by the role she plays for others within the family. Romantic love, and indeed even her sexual consent, were not required. No one asked what Persephone wanted. She was just a girl picking flowers. Demeter may have raged, but she was helpless to enact revenge. The best she could do was a stalemate.

After all, Zeus, as Persephone’s father, agrees to her abduction. Many women in the ancient world would have related to the experience of early marriage existing somewhere along the spectrum between a wedding and rape. Acceptance of the status quo was a means of survival. The Thesmophoria was the celebration of fertility but also of women’s official roles in Athenian society. Women were to be fertile, loyal, at home, and most importantly, invisible. As Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War:

Great honour is hers whose reputation among males is least, whether for praise or blame.

The Adonia was the Thesmophoria’s shadow, and it was an acknowledgement of the sorrows of womanhood. It was grounded in the body and private experiences of feminine life instead of the public performance of ideal womanhood. It was the screams of women who could not live up to the standards society set for them. After all, even goddesses couldn’t. It was the tears for real losses hidden behind a guise of girlish sentimentality for a mythical figure. It was the voiceless utterances for all that was taken and could not be spoken of. It was also a reminder of the cyclical nature of time; seasons come and go. The Adonia was the season for sadness, but it, like life itself, would one day pass. There is a terrible melancholy in knowing this life is fleeting and rotting away. There is also liberation in that knowledge, and that was the catharsis the Adonia offered the women of Athens.

Yes, I was taken from my mother at 14 and never saw her again.

Yes, my father sold me off like a broodmare.

Yes, my marriage is loveless and built on service.

Yes, I have buried my babies.

Yes, I will grow old and have to beg my son for bread,

But today, I will wear saffron!

Today, I will smell myrrh!

Today, I will dance!

Today, I will see the sea!

Today, I will wail and sing and eat with my sisters,

And no one can take that away from me!

Tomorrow, I may die, and all the terror and beauty of the world will be gone,

But today, I am alive, and in being alive I rise again like Adonis.

Upcoming Class

Learn More

Ager, Britta. “Fragrant Temples: Scent and the Sacred Landscape.” Society for Classical Studies, 2019.

Boedeker, Deborah. “Mourning and Community at the Athenian Adonia.” Classical Philology, vol. 89, no. 3, 1994, pp. 205–227.

Branham, Erin. “The Scent of Love: Ancient Perfumes.” Getty News, 2012.

Cahill, Nora. “A Hellenistic Terracotta and the Gardens of Adonis.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 76, no. 3, 2007, pp. 357–366.

Cyrino, Monica S. Aphrodite. Routledge, 2010.

Detienne, Marcel. The Gardens of Adonis: Spices in Greek Mythology. Translated by Janet Lloyd, Princeton University Press, 1994.

Lefkowitz, Mary R., and Maureen B. Fant, eds. “Women’s Festivals: Thesmophoria and Adonia.” Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation. 2nd ed., Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Saxonhouse, Arlene W. “Adonia to Thesmophoria: Women’s Roles in Attic Festivals.” The Classical World, vol. 68, no. 3, 1974, pp. 161–166.

Schaefer, Timothy. The Cult of Adonis in the Greek and Roman World. University of Michigan Press, 2014.

Parker, Robert. Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Reitzammer, Laurialan. The Athenian Adonia in Context: The Adonis Festival as Cultural Practice. University of Wisconsin Press, 2016.

Winkler, John J. “The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece.” Routledge, 1990.

.png)

Comments